Longlegs Exemplifies American Horror’s Inability to Speak to the Moment

Longlegs is only the skin of a good film.

Recently, I was having a conversation with an acquaintance on Instagram about the utter hell our species is staring down due to the increasingly dire global burning, “I’m honestly fucking scared.” I am frightened about the climate crisis and how our lives will look in the coming decades given how lacking this country is when it comes to tending to community, nurturing genuine bonds, and an ability to adapt away from the throbbing pulse of consumerism. When I say I am scared I mean materially and existentially so. My mind spins out into dark recesses about how the life of my loved ones and my own will look. This fear borders on a frightening hopelessness I always pull myself back from. James Baldwin once said, “The children are always ours, every single one of them, all over the globe; and I am beginning to suspect that whoever is incapable of recognizing this may be incapable of morality.” The children alive now and coming into this world deserve so much. We can’t devolve into hopelessness. We have a moral and spiritual duty to care for this planet and all1 the living beings that populate it. Young children coming into the world are being left with a planet on fire and an increasingly dim future. It behooves us to change our actions and fight like hell to turn this journey onto a more equitable path. Even in writing and believing this the horror of what’s likely to come continues to rap against my door.

As far back as I can remember — before I ever considered seriously becoming a writer, before I even thought of myself as someone who loves film as a medium — I have loved horror, the macabre, the grotesque. Watching Hellraiser at ten years old was a foundational experience. My mother was also a big fan of The X-Files and coming into the room when she was watching The X-Files episode “Home” (iykyk) is seared into my mind. Horror is a genre I gravitate to because it’s a pressure valve for societal ruptures, desires, and fears typically only whispered about. It can be cathartic to experience art that brings a narrative to what feels uncontrollable and unwieldy and uncontainable in life. So, why is horror so timid about exploring the piquant and definitive fears that mark our historical moment?

There’s a successfully renewed trend in the genre that blends Satanic panic vibes (sometimes directly) and religious horror hyper-focused on Catholicism. I understand the allure for filmmakers especially with Catholic pageantry and gilded ritual. Longlegs — the latest horror film from director Osgood Perkins — does not neatly fit into this trend given its more supernatural procedural with an interest in Satantic terror than a tale with a faux-feminist hue focused on a Catholic nun being exploited and clawing toward autonomy in a bloody fashion a la Immaculate. But I started to broadly wonder with the success of the return to religious focused and Satan-obsessed horror, when did we stop demanding horror scare us by speaking to our cultural moment and most deeply held fears? Bluntly speaking, who is truly scared of this shit? I’m not talking about the fleeting pleasure of a jump scare or the kind of lewd grossness that makes you uncomfortable. I mean the kind of scared that stays with you. That froths to the surface of your mind in the lonely dark. The kind of horror that is boldly entertaining but sneakily obsessed about commenting, toying with, or considering a genuine fear that exists out there in this world of ours. It doesn’t have to be my personal fears — which includes doppelgangers, ecological collapse, and body horror done against someone’s will2. I gravitate toward a variety of different kinds of horror from the gnarly, hilarious, and apocalyptic Tales from the Crypt: Demon Knight to the heartbreakingly bleak madwoman-centered works like A Dark Song and Possession to righteously wild and fun flicks like The Hidden, which includes a man getting fucked to death in a parking lot3. I don’t need my horror to always or even primarily be austere and high-minded. If anything, I prefer the opposite.

This is part of the reason I felt so drawn to Crawl when I watched and reviewed the movie when it debuted in 2019. In my Vulture review of Crawl, I discussed my relationship to nature as a Floridian from Miami and how the film taps into the fear-drenched awe toward Mother Nature I have always felt, “In Florida, you’re constantly reminded of the scope and power of your surroundings, and how small humanity can seem in the face of it. Coral snakes underfoot. Gators in the water. The clouds above hang low, apocalyptic.” Crawl is a father (Barry Pepper) daughter (Kaya Scodelario) arc wrapped in a straightforward adrenaline fueled story about that daughter trying not to be eaten by big ass gators during a hellish hurricane. I love horror that is visceral and a little nasty, bristling with surprising considerations but always primed on entertaining the fuck out of me. Which is something Longlegs failed to do. The fact that I am so giddy to talk about a film I reviewed a number of years ago over Longlegs should tell you how much I rock with Perkins’ film.

Having seen director Osgood Perkins’ other works — The Blackcoat’s Daughter (2015) and Gretel & Hansel (2020) — it is evident he is a director who excels at establishing mood and atmosphere through carefully attuned aesthetic force — textured costuming, structured framing, muted color palettes meant to evoke a world drained of something vital. But all that atmosphere and grotesque visual splendor feels remarkably inert due to stories that merely glide on the surface of intrigue and lack the kind of characterization that can lead a horror film to hook into your most tender parts. His latest film continues this trend. Longlegs takes place in the 1990s — and if you ever forget there’s usually a big ass framed picture obviously positioned in the frame of then-president Bill Clinton. The film centers on FBI Agent Lee Harker (Maika Monroe, an actress I’ve liked elsewhere including The Guest from 2014). She’s withdrawn, awkward, and struggles to retain eye-contact. She’s single-minded to the point of seeming less like an actual person and more a thinly drawn idea of one. She’s brought onto the case for her latent clairvoyant abilities. The murder-suicides she’s investigating each involve a father killing his family and finally, himself. Strange, encrypted notes signed “Longlegs” are left at the scene of the crime, with the handwriting never matching anyone in these families. This leads the FBI to believe someone else is influencing and even controlling the family to commit these murders. Each family has a nine year-old daughter with a birthday landing on the 14th, with each murder committed within a few days of this birthday. Initially unknown to her boss, Agent William Carter (Blair Underwood), Harker has a personal tie to the case. Hell, Harker herself has no idea how deep her bond with this case is and what it has to do with her religious mother, Ruth (Alicia Witt). It’s more than the fact that as a nine year-old girl in 1974 she was visited by the killer, Longlegs (Nic Cage).

Longlegs is a film with immediately recognizable care put into its imagery and soundscape. The shadows within scenes seem to pulsate with life. The mood is constituted of a discordant score, inky darkness cut with the turgid yellow light of an FBI agent’s flashlight, the pained expressions of its actors, and a sense of roiling unease. The film excels at producing a noxious vibe. But the horror film focused on the tense, intimate bond between a law enforcement figure and the serial killer they chase, is predicated upon a delicate equilibrium that requires each to bristle with bloody contradictions. The serial killer can’t merely be a tool for weirdness and violence. What does their pattern say about the world they move through, the body they live in, the forces that make it possible for them to elude capture and find fresh victims4? They need more of a thrust beyond the stylistic flourishes of the violence they inflict. Otherwise that violence loses meaning. The law enforcement officer must be branded with their conflicts, foibles, and darkness. The push and pull between them threatens to reveal just how morally and spiritually bankrupt the society that birthed them actually is. This is an equilibrium Longlegs never finds.

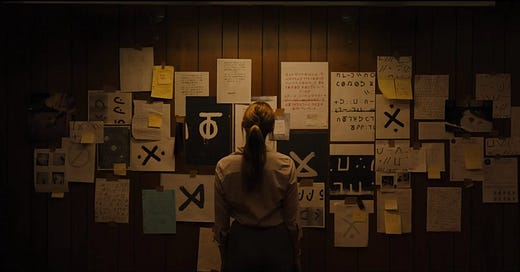

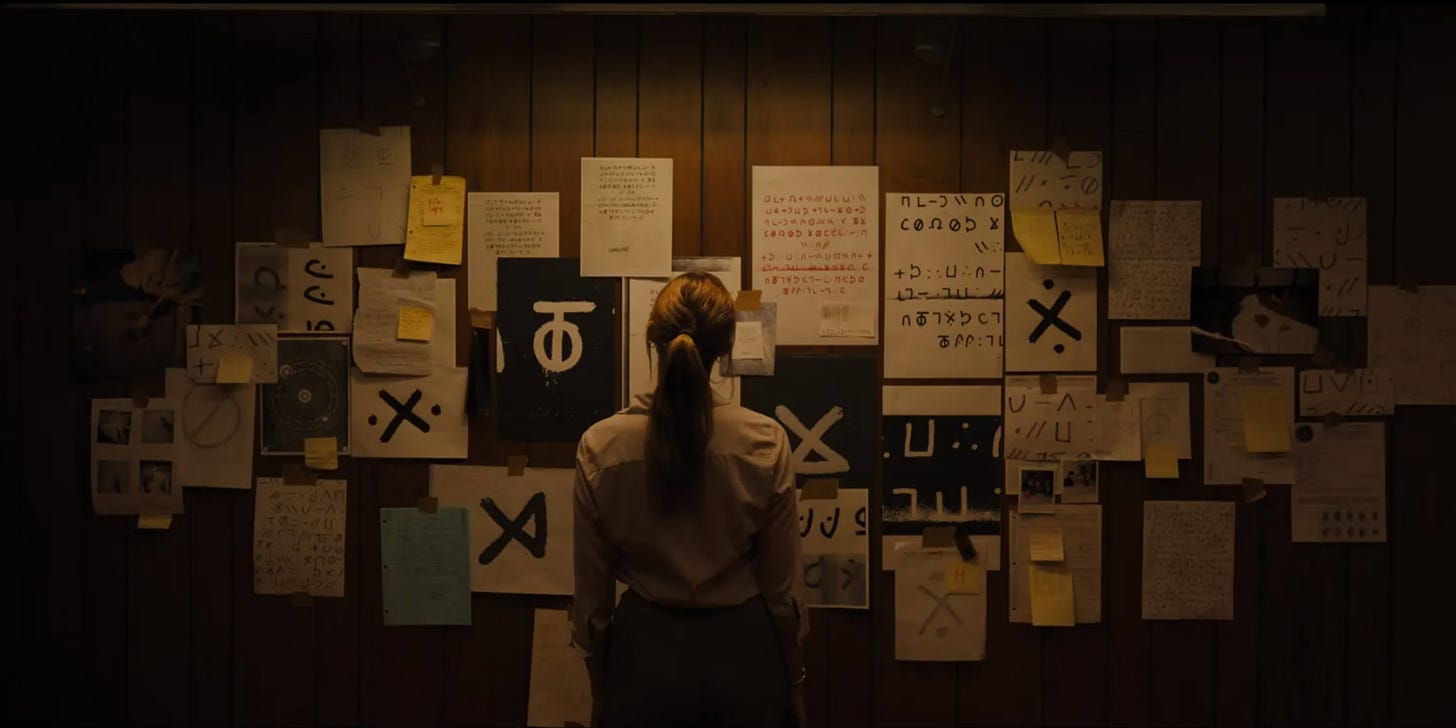

As Longlegs gets deeper into its story, the supernatural touches become more and more apparent. Perkins clearly delights in crafting the visual and sonic aesthetic of the film. Flashback scenes are depicted in the 4:3 aspect ratio. Images of coiled snakes are overlayed in the same vibrant red of the title card. But mostly the color palette is akin to a midwest winter — gray, brown, icy blue. Albeit the film isn’t midwestern, there’s really no sense of place at all. T. Rex5 is both name checked in the use of lyrics in the opening and music throughout the film. It makes a kind of sense given that Nic Cage with the thick and strange prosthetics, stringy blonde wig, and sloppily extravagant gestures seems like a cross between a decaying glam rocker and a drowning rat. Painstakingly crafted, realistic life-sized dolls of would-be victims are found. An empty metal orb in the head of each. What does it all mean? What do these narrative turns add up to? These are questions the film pricks you with but never finds actual meaning in. Visually what I kept getting caught on was the framing and blocking. Over and over and over again, characters and inanimate figures but crucial visual information are placed in the dead center of the frame. Symmetry is king. Just take a look:

This framing so obsessed with symmetry is primed to create a sense of instability. Perfection is really a flaw, here. A mask for the uncanny darkness hiding beneath the surface6.

Yet the story lacks purpose. I kept waiting for the film to reveal another layer to Harker. Any layer. I kept waiting for the violence of Longlegs to speak to something beyond his own style and interest in the T. Rex lead singer/guitarist, Marc Bolan. The end of the film unleashes an exposition dump in voice over and flashbacks centered on Harker’s mother, Ruth, that cements the film’s failures. I’ve seen it called out by people who even like the film as an uneven approach to wrapping up certain story threads. (Others, despite the import with which they’re framed, are dropped like Harker’s mental abilities.) It isn’t just that this way to communicate information is lazy and trite. It’s also empty, signifying nothing. The explanation feels threadbare. The supernatural qualities coming down to Satan made them do it. By the time I finished the film, the first thought that popped into my head was, that’s it? Watching Longlegs I didn’t feel much of anything. Not revulsion. Certainly not fear. Definitely no curiosity either. The seriousness with which its artists treat the subject matter is undermined by the very emptiness of the text. This airless lore is what the film has been holding back choosing an infodump over true exploration? Sometimes it isn't a mystery or scintillating intrigue. Baby, it’s that the filmmakers don’t have enough imagination so they leave things at the register of suggestion so you fill in the blanks they weren’t smart enough to think about.

The performances reveal this to be a film that only cares about surfaces. It isn’t a wholly bad movie — it’s too purposefully crafted and carefully braided to be bad. It’s just an airless film. The performances are capable but threadbare because they are in service of a story that stays at the surface of things. I did enjoy Blair Underwood though. His line readings and knowing glances seem ported from a movie with a more robust interest in the characters interiority, in giving them the spark of humanity. Monroe’s performance is defined by the tight way she holds her lips. It’s a performance very aware of itself. Nic Cage’s performance exists in a similar register but at least his commitment bristles with some pleasure. Even then, it’s a dated and empty idea of weirdness. It’s a performance crafted at a distance, too aware of what it needs to provoke to do so with ease. Everyone in the film is very capable at meeting the facile and obvious marks Perkins wants them to hit, which makes the performances broadly unimaginative.

Even as someone consistently drawn to fractured mother/daughter stories, the familial threads in Longlegs for its lead character are too much of an afterthought to be strong enough to hold onto. An afterthought in the sense that not once in the film do these characters feel like people with interior lives so much as figures to be positioned in the frame to produce dread that has no engine. They’re wisps of aesthetic ideas, at best. The unsettling mood the film relies upon doesn’t build or deepen. It’s a film constantly turning inward toward its own inspirations, rather than looking outward. Longlegs represents a strange impulse curdling horror. Everything is literal, over explained yet at the same time under-explored in ways that aren’t edifying but close off more intriguing readings. The renewed interest in Satanic bent horror demonstrates the paucity of the imagination in American filmmaking. This isn’t necessarily surprising given how mainstream American cinema seems hellbent on turning away from the present moment — COVID, various genocides, the crumbling of the empire that is our home — to placate us with dreams and nightmares that take us away from considering even slightly the horrors of the world we live in7.

I have seen Longlegs compared, by both detractors and admirers alike, to two films most often: Jonathan Demme’s Silence of the Lambs (1991) and Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure (1997). Both films can comfortably carry the title of masterpiece. Silence of the Lambs is so iconic it needs little introduction. The comparison is even a bit obvious in a surface level way. A brown-haired, achingly careful young woman seen as talented has a deep emotional involvement with the murder case she’s investigating as an FBI agent. But Silence has bombast and grace. It is propulsive and messy and fascinating in ways Longlegs isn’t interested in entertaining. The comparison to Cure is perhaps more apt. The 1997 neo-noir inflected horror film focuses on serial killings committed by different people. What binds these disparate crimes together is the X slashed into the bodies of the victims. These killings are committed by people dwelling in roles that are considered a moral pulse for society — a doctor, a school teacher, a police officer8. None of these killers know why they committed these heinous acts. The detective in charge of the case, Takabe (Koji Yakusho), surmises that the killers were hypnotized and controlled by a former psychology student, Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara). His motives are unclear which makes him all the more unnerving. But where Longlegs turns increasingly inward delighting in references, painful aesthetic symmetry within its frames, and flashes of style that sputter out due to the absence of thinking behind them, Cure is a film intensely invested in using horror to consider tears in the social fabric of its its Tokyo setting. Its plotting, mood, and style is an obvious forebear to Longlegs. But Longlegs struggles to produce the genuine creepiness and outright dread that marks Cure. In part because Kurosawa is a director with something meaningful and assured to say. Perkins is a director with a keen eye but he can’t seem to understand what to do with the moods he crafts. I hate the complaint of style over substance. Style is substance. Style can communicate an ideal, a posture, a belief, an emotional landscape. That’s not the problem with Longlegs. It’s an incurious film. The obsession with the detective/serial killer story exists in part because these criminals represent and speak to societal ruptures that their foil seeks to contain. If they aren’t speaking to anything but the violence they commit and the inventiveness with which they do it, then that violence becomes indulgent and chaotic.

As Chris Fujiwara writes for the Criterion release of Cure, “At the end of the film, alone at his table in a restaurant, Takabe appears to have gotten his reward. Contented, in his element, he makes small, perfect moves. He even finishes his dinner (on an earlier visit to the same restaurant, he left his plate almost untouched). The emptiness that was inside him no longer torments him; it has moved outside. In one of those masterstrokes with which a great director suddenly turns a cinematic world inside out, Kurosawa cuts to a close-up of Takabe in profile, from the opposite side of the table. A rack focus shifts our attention to the incongruities contained within the listless space of the restaurant: a teenage girl laughing with her friends at a table, the supervisor putting her hand on the shoulder of Takabe’s server as if she owned her—the main categories of social activity, leisure and work, laid out and exposed, with no principle of coherence to bind them.” With Cure, Kurosawa understands that horror is only as powerful as the real fears it chooses to tap into.

There’s two shots I want to highlight from the end of Longlegs9. The first is when Harker wakes up from a crucial confrontation in a bed in the basement of her mother’s home. The frame is flipped upside down as she crawls from the bed, trying to regain solid ground. The upside down shot has become a lazy shorthand to communicate that something is deeply amiss in the world of the film. I first noticed such a shot in the opening cityscape of the laborious 2021 Candyman reimagining. But once you clock it, it’s surprising all over the place the last few years. The second is the very end when Nic Cage’s killer says “Hail Satan” before blowing a kiss to the camera. These two shots speak to the soullessness of the film. Like so much of the film it’s empty, immature provocation. All flash, no pulse.

Thank you so much for reading Madwomen & Muses. Consider becoming a paying subscriber or donating to my Venmo, Paypal (just my first and last name) or even just sharing this piece. All such encouragement is greatly appreciated at this tender moment in my life.

Animals, marine life, human beings.

I am still pissed about watching that episode of the anime Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood.

Now that’s cinema, baby!

How the fuck did Longlegs elude capture so long when he is such an obviously dangerous creep?

Us T.Rex fans deserve better representation.

I didn’t get into this but there are so many shots that include the shadow of a baphomet, barely hidden.

This is in part to satiate an audience primed on explainer videos that consider pointing out references, busting out a few psychoanalytical quotes, and passing that off as intellectually rigorous analysis, to paraphrase Jessa Crispin of the Substack The Culture We Deserve.

Cops are a moral pulse for society but not in the way procedurals think. They demonstrates systemic rot more than anything else but rock with me here.

Don’t worry. I’m not spoiling y’all.

The audience I saw this with was mostly laughing at all its store-bought imagery. There's an element of camp here that could have saved it from being totally forgettable, but even that would require a sharper focus on the social/morally normative values that "satanism" supposedly rejects. I was waiting for a nod to the historical moment in which it was set, some kind of 90s "end of history" vibe, but it never came.

This was great, AJB. I agree about looking at today’s horror, and when you have the ecological decline, the genocides happening, and the political fuckups, some of this stuff just doesn’t compare and certainly doesn’t stay with you (see also Alien: Romulus)