On Whirlpool (1950) & The Patriarchal Allure of Being Saved

Gene Tierney gives a piercing performance in Otto Preminger's film that ultimately complicates our understanding of marriage and mental illness.

There’s an image that often comes to mind when I think of suicide. It’s that of Evelyn McHale after she jumped from the 86th floor of the Empire State Building on May 1, 1947, taken mere minutes after her death by a photography student. The photograph has a strange pull. The same pull I feel toward suicide in my darkest moments. McHale, only and eternally twenty-three, lays with such soft repose it merely looks like she’s drifted to sleep. But certain details bring into focus the violence of this moment. Namely the black car like dark crepe paper folding beneath her weight. One gloved hand holds what looks like delicate pearls around her neck. Nylons have drifted downward toward her crossed ankles.

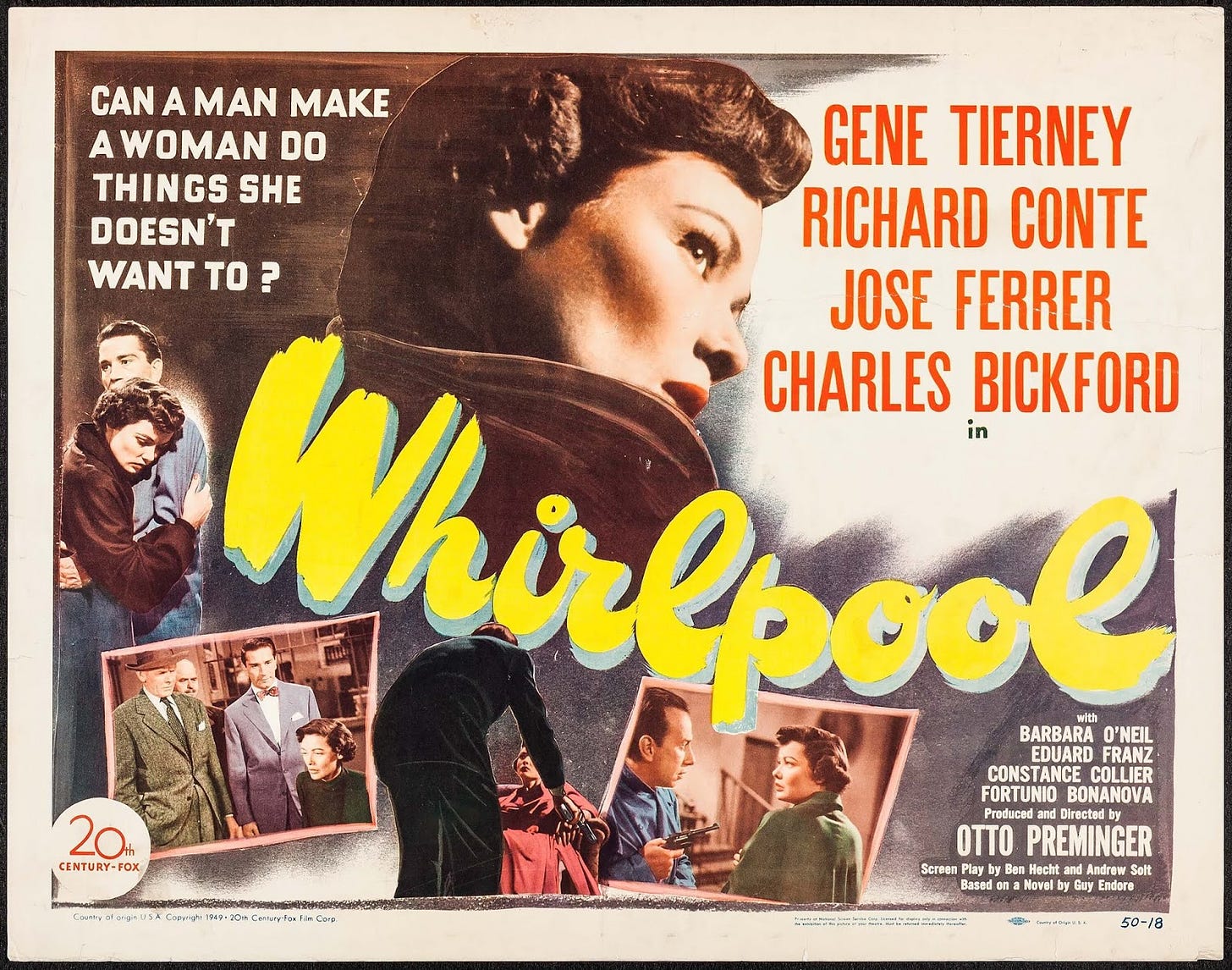

I couldn’t help thinking of Evelyn McHale when watching Whirlpool, Otto Preminger’s evocative thriller detailing the mind and tribulations of a prim housewife (Gene Tierney) who hides a secret of kleptomania from her successful psychiatrist husband (Richard Conte) and gets wrapped up in the machinations of a confidence man (José Ferrer) purporting to help her. If this already sounds wild, buckle the fuck up. In lesser hands, Whirlpool would be a frustrating, silly experience leaning more toward overwrought melodrama than the chilling appraisal of men’s control, patriarchy’s projections onto (mentally unstable) women, and some seriously tangled gender politics that it proves to be. Preminger alongside cinematographer Arthur C. Miller coupled with the richly realized image of mid-century upper class Americana the production and costume design detail, work potently to create a portrait of a woman’s unraveling and the patriarchal strictures that wed her so wholly to this suffering.

Ann Sutton (Tierney) isn’t suicidal so much as dominated by anxiety, depression, insomnia, and a deep yearning for the stability she can only project as a housewife but not fully inhabit. But there’s something to McHale’s suicide note that reminds me of Ann’s devotion to her husband, Dr. William Sutton (Conte), and deep fear about losing his love, “I don't want anyone in or out of my family to see any part of me. Could you destroy my body by cremation? I beg of you and my family – don't have any service for me or remembrance for me. My fiancé asked me to marry him in June. I don't think I would make a good wife for anybody. He is much better off without me. Tell my father, I have too many of my mother's tendencies.” McHale’s suicide note speaks to an internal complication and familial history we will never fully understand. But there’s something especially heartbreaking beneath its tender words that speaks to the pressure of marriage and womanly performance.

In Whirlpool, Ann, too, has a familial history and womanly expectations weighing upon her present journey. Her interior life is defined by a deep well of shame over her past, her kleptomania and her fear that she is unable to be the wife she feels her kindly (and pleasantly boring) husband so deserves. It’s in that last expectation that the film becomes imbued with an intriguing current of criticism toward the American imagination’s narrow conception of marriage and the heaviness this belief thrusts upon a woman’s psyche and reality. Ann’s well of shame prohibits her from turning to her husband for help. Is it any wonder she gets involved with José Ferrer’s forcefully charismatic confidence artist who claims to help people with untraditional means in a more holistic way than psychiatrists like her husband are able to do. Those untraditional means happen to be astrology and hypnotism. (There’s something cutting about his astrology being viewed as a tool for manipulation given the cultural climate I’m watching it in today.) After helping Ann skate past an arrest when she’s caught stealing from a well-to-do department store, David Korvo (Ferrer) is able to manipulate her to his own ends under the guise of care. And those ends are far more dangerous than mere blackmail, which she first suspects him of.

The evidence of Korvo’s deviousness continues to add up from the moment he cuts a path through the department store straight to Ann’s side, situating himself as her knight in shining armor. Theresa Randolph ( Barbara O’Neill), another rich woman connected to the other rich ass people Ann comports with given her class, is a tough broad with a shock of white hair framing her temple who warns Ann at a party that Korvo is not to be fucked with. She doesn’t mince words. He targets rich women and takes them for all they are worth under the guise of care. Ann defends Korvo as he’s her only source of comfort and means to regain her autonomy. But much of the terror imbued in Korvo’s character comes not from the often wild script (gallbladder surgery plays an important role!) but in Ferrer’s genuinely dope as hell performance. Watch the way he sizes people up as if he’s looking for an appropriate wound to press. Listen to how words slip from his lips the way a poisonous snake’s tongue dances in the air. Catch how quick he shifts from graceful chivalry to swift anger when he doesn’t get his way. But Ann longs for betterment and the ability to protect her marriage from her own internal demons. The gravity of Korvo’s manipulations — which lead Ann to an arrest only her husband’s love and her honesty can save her from — becomes truly evident later in a remarkable sequence that relies on Tierney’s skillful physicality and Preminger’s graceful camerawork to succeed.

Roughly halfway through the film is a sequence that begins with Ann abruptly stopping a letter she’s writing to Dr. Sutton in their home as if a switch has been flipped in her mind. As she progresses with curt movements through her home — not exactly mechanical but abbreviated — and her eyes have a glazed affectation, two things become evident: Damn, Tierney can act! and Oh, shit she’s hypnotized!! Ann dreamily moves from room to room, swiping the recordings of Theresa Randolph’s psychiatry sessions with Dr. Sutton after she left the “care” of Korvo, before getting into her car and driving through winding, mountainous paths. The score swells with intrigue, its sharp strings and bombast often cue us into the war within Ann to be the woman she so desperately wants to be for her husband. This is all well done but what makes this sequence is its endnote.

Ann finds herself, still hypnotized, making her way through a stranger’s grand home. She hides the recordings in a closet. Down the long staircase she goes into the hearth of the home. The camera swoops down with her crossing behind a mantle place before turning to its front at which Ann stands. A detail then comes into view of a portrait of the grand mansion’s owner: Theresa Randolph. Just when you’ve caught your breath from the swooning camera work, another reveal comes into view with the camera’s swimming movements and the sleek editing: Theresa’s dead body. Before Ann can even come out of her hypnotized stupor she’s caught by the security guard and swiftly put into the hands of the police headed by the thorough and recently widowed Lt. James Colton (Charles Bickford), whose slip of backstory and outlook prove vital for Ann’s freedom. It’s here that the film comes into its own, uncovering knotted territory about mental illness and marriage.

Much of what powers this film is its splendid use of misdirection — visual and narrative. With Korvo’s curious earlier actions coming into better focus in the latter half. Due to his maneuvering (and Ann’s silence over the truth), the cops and even Dr. Sutton believe Ann was cheating with Korvo instead of being treated by him. The moments that caught me in the second half are often in the margins and easily missed. When Ann is coming out of her hypnotized state and starts to piece together the situation she’s in, Lt. Colton asks a doctor he has on staff if she’s fit to stand scrutiny. The doctor is only one small part of the film’s visual business in this scene but I couldn’t take my eyes off the way he looked at the back of her head with such intensity. It was as if he thought staring at her could garner the truth. But the only truth men like that need is the one they can glean from what they already see.

Ann is thrust into jail as Dr. Sutton tries to save his wife from prison and herself. Despite the evidence he knows Korvo ain’t to be trusted. But everyone else believes Ann guilty and mad and untrustworthy. She’s called a liar more than once. Her own fragile emotional state is disrespected. All I could think when watching it was just how dumb these men were. They think they understand Ann. They only see their own projections. Tierney made a career out of navigating the projected desires of men. But perhaps that’s true of every actress. “There’s something wrong with me. Help me. Please!,” Ann pleads with overheated longing to Dr. Sutton, those lonely and lovely eyes beaming up toward the camera. If Ferrer dominates the camera, moving against our expectations by defining his character’s physicality with a slippery and wily forcefulness. Tierney trembles in its presence, vibrating with anxiety throughout the film.

On the surface the film’s answers about Ann’s psychology — what led to her kleptomania and trusting a man like Korvo — are frustratingly simplistic and regrettably Freudian. Which of course isn’t surprising considering the rage in Hollywood at the time with psychology. The film loses a touch of its intriguing complication when it all comes down to daddy issues. But such a narrative decision does speak quite thoroughly to the cultural mood and beliefs of the time, some of which still fester today. “I’ll cure you, Ann,” Dr. Sutton says to his wife with such tender eyes and an assured voice. And she so wants to be saved. It’s such a fantasy, but whose? “I love you as you are,” Dr. Sutton says in the same conversation as he continues to coax her into remembering what happened in Theresa’s home going so far as to return her to the scene of the crime with Lt. Colton. In many ways I see the desire to save a mentally ill woman from herself as deeply patriarchal and patronizing. I’ve seen such beliefs taking shape through the actions of men I once knew. They always think you want to be saved as if that’s possible or even desirable. But it’s a seductive fantasy; one in which the cultural, personal, and physiological circumstances that lead a woman to struggle with mental illness can easily be healed by the love of a good man. This isn’t to say I don’t want or need to be held and loved and respected. But I damn sure am not courting a savior. I’ll save myself.

After being enraptured by the film, I turned to Gene Tierney’s 1979 autobiography written with Mickey Herskowitz. I was curious if I missed Tierney discussing with Whirlpool or even Leave Her to Heaven (1945) what it is like to play madwomen when you’re navigating that experience in your real life. Tierney doesn’t get into that conundrum but she does limn the dynamics of failed loves with the likes of JFK and Prince Aly Khan, her work, motherhood and how these aspects of her life had been shaped by her struggle with mental illness, which led her in and out of hospitals for so long. I was really struck by this passage, which comes after she details stepping out on her apartment’s ledge one day and being forced back into the hospital again:

“For months I had lived in dread of returning to a sanitarium. I had been locked in rooms no larger than a cell, with bars on the window. I had tried to escape and was chased and pounced upon like a dog. I had been subjected to electric shock treatments that deadened my brain, stole chunks of time from my memory, and left me feeling brutalized.”

Tierney may not lavish her acting techniques and her view on her actual roles with much attention but it is evident in her performance of Ann Sutton that she was keenly aware of bringing to the forefront through her physicality, voice, and gaze the claustrophobic nature of being a woman at war with her own mind.

One of the best touches of the final scenes in the film is how they position Theresa’s portrait within the frame and the use of her recorded psychiatry sessions detailing Korvo’s physical and sexual abuse becoming essential to the sonic dimensions of the conclusion. It makes her a ghostly figure hovering over the ending, a valuable reminder of just how deeply a confidence man can hurt the woman he’s made his mark. Even though the film seeks to reaffirm the audience on the institution of marriage and women’s place within it, there’s a sense of unrest to the beautiful image of marriage that the film ends on. “Nice to have a wife to come home to you,” Lt. Colton tosses aside as Ann and Dr. Sutton passionately embrace. But just when you have a handle on the note Preminger is ending on, Lt. Colton makes a call “to pick up a body”. Ending with Lt. Colton and the violence of his final line being foregrounded strikes a note of ambivalence laced with the remembrance of Korvo’s danger and death. Perhaps, the film’s observations about marriage and womanhood, mental illness and the wounds we walk with aren’t so stable after all. Perhaps, there’s no single answer we can find as to why we madwomen are the way we are.

Thank you! I’m happy I moved to Substack too and I’m looking forward to writing more frequently when it comes to my newsletters. Glad you enjoyed the piece!

hey! hunter harris's newsletter brought me here and this was such a wonderful read. never saw the movie, going to see it right now.